How diary excerpts became the voice in a book about eating disorders

How diary excerpts became the voice in a book about eating disorders

By June Alexander

Excerpts shared by 70 diarists for my book, Using Writing as a Therapy for Eating Disorders—The Diary Healer, told compelling stories of struggle and courage. Each of the diarists, like myself, had experienced an eating disorder. My challenge was to locate leads within the stories, and combine them, through paraphrasing and selected quotes, into one fluid text.

I needed to identify with each story but remain sufficiently detached to maintain overall focus. To avoid feeling overwhelmed, for my database had accumulated more than 300,000 words (~ 1,000 pages double-spaced), I needed to be confident in absorbing testimonies that spoke to me and ignoring those that did not feel true to my instincts.

Major leads included stigma, secrets and trust, sexual abuse, the influence of the Internet on diary formats, and poetry. These were not new leads, but the diaries presented their origin and impact in a new light. To address them I adopted a reflective process with self, other diarists, experts in the field and my manuscript readers.

My major themes for maintaining focus comprised:

- A diary, in the context of my research limitations and focus, is a recording tool that can help the writer to connect with thoughts and feelings.

- There are many ways of keeping a diary.

- The essence of a diary is about being a friend with self but when you have an eating disorder, avoidance may kick in and lead to layers of secrets and deceit, not only with friends and family but also with the diary.

- Secrets affect ability to be true to self and to others and secrets, of which the diarist is not consciously aware, such as an eating disorder, can be particularly sinister. Here, the diary can provide a therapeutic bridge.

- A diary may become the basis for a memoir or other type of publication – however there are many considerations.

A transparent and collaborative process, which involved reflection in my current diary, regular online correspondence with the diarists, face-to-face meetings and networking with academics in the field, and constant emailing with my manuscript readers, helped to ensure leads were thoroughly explored. Often, introductions and chance meetings at conferences – including encounters in lifts and during session breaks – or suggestions or key words followed up on the Internet, led to new perspectives and meaningful dialogues. For example, secrets were part of my illness for so long they seemed intrinsic to life, but discussion prompted the observation that secrets were a major issue, leading to a dedicated chapter, “The role of secrets – how the diary can dupe you.”

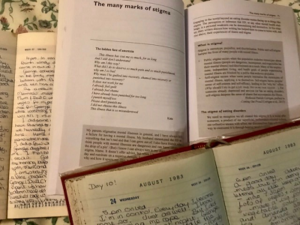

The many marks of stigma

Stigma was another issue that seemed inseparable in the life of someone with an eating disorder. However, discussions helped me to see that diary excerpts could illustrate the effects of both public stigma and self-stigma, leading to the chapter, “The many marks of stigma.” I delved beyond evidence recorded in the diary entries to develop an argument for diaries to be used as a form of sharing and thus a means of replacing the tendency for secrecy, self-shame, isolation and continued distress, with more self-affirming thoughts.

An alternatively objective and subjective approach, that is, considering standpoints in terms of both facts and feelings, helped to ensure comprehensive exploration of deep-seated factors. Some diarists observed that the reflective process of reading back over their diaries to select entries to share with me had helped them to see how far they had come in their recovery, and to see the illness more in the context of their life rather than being their life. My manuscript readers, meanwhile, were helpful for contemplation of ideas during this frequent reflective, back-and-forward, writing process. An example was the poetry finding. I, personally, had not found refuge in poetry, but it had been a helpful coping technique for other diarists. To incorporate a chapter to explore why some diarists found poetry useful necessitated the reassessment of other content and to make room for the poetry, an early chapter on history was deleted.

Layers of secrets

Many submissions that I received from participants made it clear that their eating disorders formed around, and were built on, layers of secrets. This issue of secrecy has been explored in the literature, and it became apparent to me that secrecy, functioning as a form of avoidance and self-denial, was driven, in turn, by the complex ego-syntonic and ego-dystonic factors that create tension and internal ambivalence in many people with eating disorders. For example, an ego-syntonic (calming and acceptable) thought, “I will try to take each meal as it comes and not overthink it” could be countered by an ego-dystonic thought (intrusive, difficult to resist), “I must exercise for 10 minutes for each bite of food I take.”

Moreover, self-generated thoughts that appeared to support healing, but in fact promoted secrecy, such as “I ought not talk too much about my fears about food in case I cause concern in others” could also be reinforcing the eating disorder by delaying or even sabotaging recovery. The confusion between ego-dystonic and ego-syntonic symptoms may also be intensified by ever more complex and self-defeating patterns of ambivalence. For example, one might be reluctant to extricate oneself from an abusive romantic relationship because its traits, such as manipulation and domination, are aligned with and maintained by one’s relationship with an eating disorder: “If I end either or both relationships, I will have to face life without either or both relationships, and the emptiness that accompanies this thought is simply terrifying.” In these ways, secrecy is pivotal to sustaining an eating disorder, and awareness of its power is pivotal to change. Accordingly, I concluded that discussion on secrecy in the book might be useful in raising awareness in readers about the types of secrets that are helpful, and others that compound the illness.

Constructive and destructive thoughts

Perhaps the most profound evidence of these secret thought challenges was revealed in the way entries chronicled the diarist’s trust in the diary as a friend of self, but when the illness developed, the entries showed the diary inadvertently assisting disintegration of self by listing and emphasizing the eating disorder’s rules and demands. Thus, a diary can help to give voice to both constructive and destructive thoughts. This insight is important for readers to appreciate and this is sometimes a painful process. Learning to distinguish between them by noticing one’s own emerging feelings in the written word contained in a diary, rather than relying on the powerful, familiar and internal voice of the eating disorder, is vital. Consequently, I concluded that discussing these important nuances and processes in the book might be useful in raising awareness in readers about the advantages and disadvantages of keeping secrets while combating an illness that tends to be insidious in defining its own boundaries according to its own expanding set of rules.

Exposing entrenched beliefs

Constant checking of the context of excerpts with diarists was important, not only in relation to secrets and trust, but also in exposing deeply entrenched beliefs that stemmed from traumatic experiences such as childhood sexual abuse or misdiagnosis of illness symptoms. My challenge was to tell the story through the diarists, balanced with insights from evidence-based research. To relate only the diarist’s story could provide a powerful and sensational individual account, but possibly a misleading one generally. For instance, if one or more diarists had experienced sexual abuse, this did not necessarily mean most people with an eating disorder had experienced such abuse. Conversely, there were many people who experienced sexual abuse who did not proceed to develop an eating disorder. I aimed to be objective, balancing diary entries with current evidence-based findings, in a way that spoke primarily through the diarists.

Evidence of the impact of living with an eating disorder featured in each diary entry. My challenge was to retain the essence and portray the lead messages in these candid accounts and, concurrently, explore them through a lens of empirical knowledge. The practice of reflectively pursuing leads required gathering, compiling, sifting and a re-gathering of the many parts that contributed to each topic, to produce a smooth flowing narrative. The guiding principal, always, was for the content to address how diary excerpts could be used in writing a book to assist people with eating disorders.

For more information, see Using Writing as a Therapy for Eating Disorders—The Diary Healer, the creative work in my PhD (Philosophy).