“Aunt June, you are the problem in our family:” Using the journal to dispel stigma, inside and out

“Aunt June, you are the problem in our family:” Using the journal to dispel stigma, inside and out

by June Alexander

Engaging in the world beyond an eating disorder (ED) means facing up to things like stigma. The perception or inference by others that ED, or any other mental health challenge, is a personal weakness can be demoralizing and destructive. In this post, drawn from my book, The Diary Healer, diarists discuss how writing has helped them to come to terms with, and rise above, their experiences of shame and stigma.

What is stigma?

Stigma is stereotype, prejudice, and discrimination. Public and self-stigma hamper the lives of many people with mental illness. Professor Patrick Corrigan, in the preface to Coming Out Proud (2015) explains:

* Public stigma occurs when the population endorses stereotypes about mental illness (people are dangerous, incompetent, and responsible for their mental illness) and discriminates as a result. Many of the employment, independent living, and health goals of people with mental illness are blocked by a public that endorses prejudice.

* Self-stigma occurs when some people internalize the stereotypes of mental illness, applying it to themselves. Self-stigma harms peoples’ sense of self-esteem and self-efficacy leading to the “why try” effect. (“Why should I try to get a job?” “Why should I try to study?” “Why should I try to live on my own?” “Why should I try to recover?”….).

For someone already depressed and anxious, or has an eating disorder, self-stigma deepens the sense of shame that accompanies the illness. Associate Professor, Paul Rhodes, describes the stigma of eating disorders in this way:

“We need to recognise we all created this stigma; it is a social phenomenon, a product of our superficial, performance-oriented culture, our collective unease with affect, our disconnection from self. The best way to overcome it is through hearing people’s stories.”

To be stigmatized is literally to be given a mark or brand that signals disgrace and, at best, second-class status in a society. In many so-called modern and developed societies the label of “mental illness” is stigmatizing because it is viewed as a euphemism for “crazy,” “wacko” or “truly weird.” Often even the ostensibly humane label “mentally ill” carries stereotypical beliefs and negative emotional reactions (for example, fear, disgust, pity, and opportunist exploitation) that revolve around being childish and immature, weak, irresponsible, unworthy of inclusion, dangerous or out of control.

My eldest nephew, as a young adult, pronounced: “Aunt June, you are the problem in our family.”

The double challenge

The perception of others, when accompanied by self-acceptance of the stigma and its stereotypes, can hamper healing. Derogatory labels from others peppered my diaries. I noted them as if to confirm and affirm the equally derogatory labels of my own.

Together they demeaned and shot holes in my identity, and strengthened my illness.

At vulnerable times, in family, relationship and work environments, I felt I deserved all critical name-calling, and often my behavior reflected this. When told “you are the problem” often enough, it is easy to start believing it, and become “the problem,” imprisoning you more within ED and isolating you further from self. Doctors had to work hard to convince me that I was not neurotic and that I was genuinely sane and worthwhile. Therefore, in many ways, recovery had to include re-storying of perceptions as both participant and observer of self.

Suggestions that an eating disorder is a personal weakness can contribute to a rapid buildup of shame, alienation, and hopelessness. The effect is especially damaging when occurring in the very places you expect to feel safe and unjudged, like in your home and a healthcare environment. Maddy explains how easily it can happen:

“I was getting out of bed for my six o’clock dinner, and a female nurse came in to supervise. She looked and said, ‘You don’t look that thin, I mean, you are short, so for your height you don’t look that thin and don’t look anorexic.’

I was too scared to tell her how hurt I felt because I am always worrying about if people like me. Afterwards, I wanted to just run away, but was too worried about disappointing my family.”

Reading narratives of how others have coped with mental health challenges, and embodying their insights into your own life story, can help to dismantle and eventually reject unhelpful ways of thinking. The process, the “doing,” of writing a diary and reading stories about developing, living with, and maintaining a sense of self separate from the illness can assist the gradual but essential shift in the social construction, and re-storying of harmful beliefs.

Stereotypes and fallacies

Beyond the perception of self and close others, wider powerful cultural beliefs and practices can reinforce misguided notions that “thin is good” and another stereotype, “fat is bad.” Such “in your face” inferences can hinder recovery from ED. Another cultural misconception is that only young people have eating disorders. Adults suffer, too—often since childhood and often in silence, feeling too ashamed to share their secret and seek help (see, e.g., Maine et al., 2015).

Jenny, 38, until she heard my story, thought she was the only adult with an ED. Her greatest sadness was the passage of years had led some family members to misunderstand her illness behaviors, at times alienating her from their life. Equally, if not more damaging, are misconceptions in the health services environment. During a relapse requiring inpatient care, Jenny overheard a nurse, standing outside her room in the corridor, say to another nurse: “You would think she would be over this by now, wouldn’t you.”

Community-based prejudice and misconception

Besides the illness itself, stereotypes around race, gender, color, culture, ethnicity, immigrant populations and class may preclude you from feeling like you belong, and lead to stigmatization. In this way, community-based prejudice and misconception aggravates the isolating aspects of an eating disorder. Even being educated and “good looking” can add to your problems. I was told: “You are intelligent, you have a lot going for you, surely you can see this is holding you back? Why are you being weak in this one area?”

Doctors and friends considered Andrea, a diligent and bright student, “too smart” to have an eating disorder. They could not seem to understand that, as with the onset of any serious illness, logic had no role in the development of her eating disorder, or in continuing to elaborate and carry out its cognitive, emotional, and behavioral demands. It is true Andrea did place ultimately destructive expectations on herself, but even her high level of intelligence and scientific problem-solving ability did not enable her to understand either how she “knew” what she needed to do to recover or why she was unable to put those healing behaviors into practice. She stepped out of the resulting harsh self-judgments and intense frustration by writing in her journal about her irrational thoughts and behaviors and, paradoxically, finding logic and hope in the irrational. For example, Andrea began to understand what purposes her ED was serving in her life.

“You don’t look like you have an ED”

Bingeing and purging caused Angel to feel “incredible” shame. She also felt stigmatized— branded or stained with disgrace—because she could not control, let alone stop, the cycle. The result was an unhealthy compromise with herself and others: Angel was often comfortable talking with health professionals and friends about her anorexia nervosa, but became secretive about more bulimic-type behaviors. She looked “normal” and felt expectation to behave so; the pressure was great. During this difficult phase, Angel’s diaries became a trusted place to troubleshoot an instance where she had binged and purged and to make a written commitment not to do it again.

Making such disclosures in her diary helped Angel get the problem outside her mind, and the resulting distance and perspective helped her to feel more hopeful while easing humiliation and guilt. Other times, the process of describing the situation in her diary enabled her to locate, identify and analyze the emotion behind triggers, then commit to attending to the emotion as a way of minimizing or avoiding those triggers. “This approach,” Angel explains, “allowed me to feel okay about having binged/purged, and hopeful that I wouldn’t do it again.”

Further reading:

Using Writing as a Therapy for Eating Disorders—The Diary Healer by June Alexander

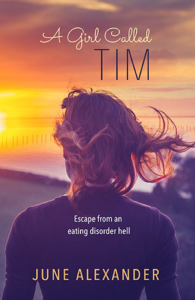

A Girl Called Tim (Kindle) by June Alexander (memoir)

References

Alexander, J. (2016). Using writing as a resource to treat eating disorders: The diary healer. Hove: Routledge.

Corrigan, P., Larson, J., & Michaels, P. (2015). Coming out proud to erase the stigma of mental illness: Stories and essays of solidarity. Collierville, Tennessee: InstantPublisher.

Maine, M. D., Samuels, K. L., & Tantillo, M. (2015). Eating disorders in adult women: biopsychosocial, developmental, and clinical considerations, Advances in Eating Disorders, 3:2, 133-143, DOI: 10.1080/21662630.2014.999103