The story behind this website

The story behind this website

The story behind this website began when I was 11 years’ old in 1962.

Early that year, I developed an eating disorder but a gift of a diary at Christmas seemed to offer a reprieve and give me comfort and hope. Writing helped me to feel better. Words were like good friends – they were always there for me and did not judge.

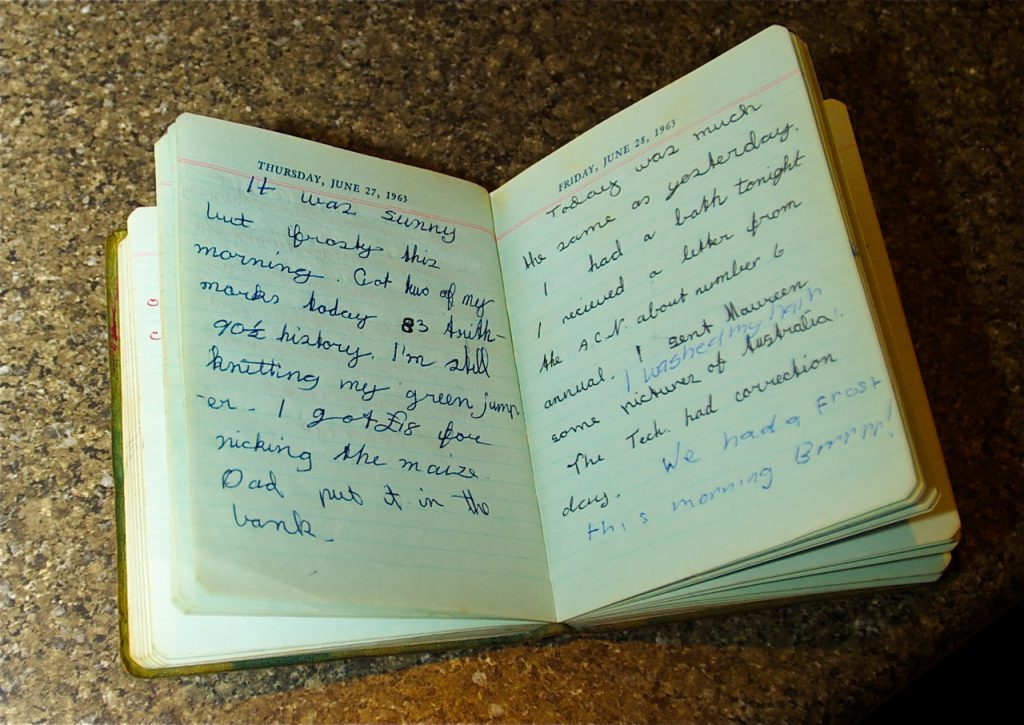

The diary provided somewhere to offload confused thoughts and store the calorie numbers, and food and exercise rules, that were cluttering and dominating my mind. The pen and paper provided an external connection to my inner self, creating a tangible recording tool. In this way my diary, like the eating disorder, became a coping mechanism for easing anxiety and trying to manage the demands of daily life. Becoming what seemed an immediate, trusted friend, my first little diary marked the start of a literary journey that, over the next 40-plus years, would chronicle the disintegration and reintegration of my identity and self.

About my diary

My first diary entry is crammed with detailed records of food consumed, exercise routines, the time of awakening and going to bed, and sport results. In the months and years that followed, more self-expression became evident. In adolescence, words tumbled onto the pages as I tried to make sense of conflicting thoughts and feelings. The limitation of my diary’s one-day-to-a-page was often a challenge – my handwriting would reduce in size to make space for more words as the end of the page approached. My private world comprised the diary and me. Not for many years would I learn there was also the eating disorder, and that the diary’s influence extended far beyond the two of us.

The eating disorder, like the diary, thrived on privacy—and encouraged the keeping of secrets. As I progressed into adulthood, the diary became a refuge in which to express and analyse thoughts and develop coping strategies. The pages recorded determined efforts to gain self-control and freedom from what seemed the food monster. Alas, every fresh start was quickly followed by yet another crushing failure.

I was unaware that confiding in the diary was also strengthening the eating disorder, with its unrelenting and stringent demands embedded on every page. Nothing I did was enough, and the impossible-to-keep rules of the illness became shameful secrets within secrets that had to be guarded and hidden from others. By age 28, my diary had documented an almost complete disconnection of self from body and increasingly I was losing the will to live.

A voice when one cannot speak

Outwardly, I masked my illness. I was high functioning. People commented on ‘how well’ I managed a busy life. I was a wife and mother-of-four with a full-time journalism career, but my diaries of that time reveal a desperate daily inner struggle to honour daily lists and pledges revolving around weight, exercise, and food intake. After 17 years of struggling privately with these unrelenting demands, desperation fed by suicidal thoughts and fears of insanity drove me to the edge. My children were my saviours. My love for them, my desire to see them grow up, gave me the strength to reveal the shameful thoughts confined to my diaries to a doctor for the first time.

Upon learning I kept a diary this doctor, and others who followed, encouraged me to continue my diary writing as a coping tool. For six years, doctor after doctor did not know how to address my illness but they could see that writing was a lifeline for me. However, like me at that time, the health professionals were ignorant of the diary’s potential to play a pivotal role in my illness, and of its ability to be a foe as well as friend.

Eventually, in my 30s, a psychiatrist saw ‘me’ beyond my illness, and gained my trust. He noted that I could express myself more clearly in writing than through speaking. Decades of stigma, shame, and ignorance and misunderstanding by close others had silenced my ability to share thoughts and feelings orally.

When the diary becomes a self-healer

The psychiatrist suggested my diary entries could assist the healing process—that is, of delving through repressed layers of emotion to reconnect with my healthy self, and of disconnecting from my eating disorder self. I was encouraged to draw on the diary entries as a means to engage in written communication. So began a long psychiatrist-patient relationship whereby I would arrive for my new session, clutching several foolscap pages of handwritten diary extracts. I would sit silently while the psychiatrist read my outpourings and then our verbal session would begin.

Gradually, under my psychiatrist’s therapeutic guidance, what I wrote in my diary began to reconnect with authentic thoughts and feelings. The eating disorder’s demands began to fade. Self-abuse and self-harm gave way to self-care as my body and mind progressively reintegrated. Gradually I regained my healthy self and found my voice. Decades later, at age 55, upon healing sufficiently to re-enter life’s mainstream, I departed my journalism career to reflect on these decades of diary writing in a memoir (A Girl Called Tim) about my illness experience. Letting my inside story out was to change my life….