Using journaling to recognize self-harming behaviors and reclaim your own voice

Using journaling to recognize self-harming behaviors and reclaim your own voice

The Diary Healer, Page 56

by June Alexander

Knowledge is power in healing from an eating disorder. But when you do not understand that you are sick, the illness may thrive, isolating instead of connecting you with helpful others.

At some innate level, you may know your real ‘healthy-self’ is ‘there’, or you may think this is how life is: that the way you feel right now is normal. You may realize you have ED symptoms, but don’t know how to free yourself from them.

Ruby’s eating disorder became more challenging when an associated amphetamine addiction developed from her attempts to suppress appetite. The amphetamine abuse caused Ruby to experience long stretches of insomnia. Days and nights became filled with a growing preoccupation with her own thoughts, coupled with the return of painful but uncontrollable memories of former traumas she had never dealt with. Then, Ruby began to keep a diary.

With relentless taunts from the ED ‘voice’ pervading her every moment, Ruby ended up unemployed and homeless; eventually, her thoughts became as chaotic as her life. Cluttered thoughts clamored in her bid to make sense of her past, her current situation and her rapid demise. To focus on any one thought or to separate thoughts and feelings, or even to put memories into a chronological order, was impossible; everything, Ruby said, ‘just blurred together and formed a kind of overwhelming white noise’.

But Ruby persevered:

“I began to write each thought and feeling out as best I could and I slowly started to put them into an order to try and make sense of everything; I began to work out how everything had unravelled. It was a bit like putting a puzzle together. And all of a sudden I had this journal – a tangible document I could point to and say ‘this is what happened’, ‘this is where it started’, ‘this is how I feel’ and I could start to articulate what had previously just been a jumble of confusion. As well, I could start to document each new experience. As the words went down on paper I felt I could let go of the many thoughts in my head just a little, because now they were written down, they would not be forgotten or lost. I’d been worried that if I stopped thinking about them, the thoughts would be lost forever. Journaling was the first time that I had found a behaviour other than self-harm that could make me feel better.”

Ruby

Poetry enabled Ruby to tell her story to her diary and therefore to herself. This form of narrative eventually helped her to put ED and past traumas in the context of her life:

A flashback here, a memory there, A childhood that wasn’t fair, A growing feeling of despair, I’m damaged goods beyond repair.

A guest of ours was high and pissed, She climbed on me and pinned my wrists, My housemate didn’t give a shit, Guess I should just get over it.

Constant thoughts of suicide, And of my two good friends that died, And god knows just how hard I’ve tried To put my world of hurt aside.

A new voice soothes me every day, It vows to take my pain can away, If I just decrease what I weigh, Which seems an easy price to pay.

But with each kilo that I lose, The voice just gives me more abuse, And I’m too scared now to refuse, And there’s no better path to choose.

My health concerns are getting vast, I’ve now commenced a 10 day fast, Some stimulants will help me last, And keep my mind off my past.

A day that seems to never end, I haven’t slept since last weekend, I’ve starved myself since god-knows-when, I’ll do it all next week again.

I take some pills to dull the pain, I cut myself to feel again, I feel as if I’ve gone insane, I guess there’s no way to explain.

My EDs getting more severe, My family now don’t want me here, I’ll lose weight till I disappear, No-one will even shed a tear.

The hospitals showed me their door, I don’t have housing anymore, I’m sleeping on a dirty floor, I am the undeserving poor.

Full of dread and angst and hate, I’m in a pretty fucked up state, Any help has come too late, The voice insists I lose more weight.

I stay awake both day and night, I see strange things through blurry sight, Now everything is black and white, No middle ground, no wrong from right.

I take more drugs, I barely eat, I pass out walking down the street, The voice will not let me retreat. And I’m ready to admit defeat.

But the voice that’s in my head, That makes me wish that I was dead, That leaves my self-esteem in shreds, Is my own thoughts and my own dread.

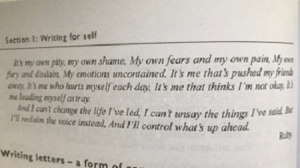

It’s my own pity, my own shame, My own fears and my own pain, My own fury and disdain, My emotions uncontained. It’s me that’s pushed my friends away, It’s me who hurts myself each day, It’s me that thinks I’m not okay, It’s me leading myself astray.

And I can’t change the life I’ve led, I can’t unsay the things I’ve said, But I’ll reclaim the voice instead, And I’ll control what’s up ahead.

Using your diary as a self-navigator

Writing in your diary can help you find a way when others might think you are self-centered or ‘lost’. Reading works by experts in this narrative medicine field (for examples, see Bolton; Pennebaker; and White and Epston in Recommended reading) helped me to understand why I have preferred writing to, rather than talking with, therapists and family throughout my illness and why writing has been pivotal not only to recovery but to creating a life beyond the illness.

ED secrets, when buttressed by starvation, chaotic eating and inadequate nourishment, can form a wall between your life’s narrative and emotional truth. Pouring feelings into your diary, in whatever form feels right, can help sustain life until bit by bit you can adequately nourish your body, and gain the skill to examine emotions, follow them to their source, and link them to events in your life.

Next week: Letter-writing

Reference

This post in drawn from Chapter Eight in:

Alexander, J. (2016) Using Writing as a Resource to Treat Eating Disorders: The diary healer, Hove: Routledge.

Recommended Reading

Bolton, G., Field, V., & Thompson, K. (Eds.). (2006). Writing works: A resource handbook for therapeutic writing workshops and activities. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Bolton, G., Howlett, S., Lago, C., & Wright, J. K. (2004). Writing cures: An introductory handbook of writing in counselling and therapy. New York, NY, US: Routledge.

Epston, D., & Maisel, R. (2009). Anti-anorexia/bulimia: A polemics of life and death. In H. Malson & M. Burns (Eds.), Critical feminist approaches to eating dis/orders (pp. 210–220). New York, NY, US: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Maisel, R., Epston, D., & Borden, A. (2004). Biting the hand that starves you: Inspiring resistance to anorexia/bulimia. New York, NY, US: WW Norton & Company.

Pennebaker, J. W. (1997). Opening up: The healing power of expressing emotions (revised ed.). New York, NY, US: Guilford Press.

Pennebaker, J. W., & Chung, C. K. (2007). Expressive writing, emotional upheavals, and health. In H. S. Friedman & R. C. Silver (Eds.), Foundations of health psychology (pp. 263–284). New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press.

White, M., & Epston, D. (1990). Narrative means to therapeutic ends. New York: WW Norton & Company.