About A Girl Called Tim

About A Girl Called Tim

I waited until I was almost 60 (a grandmother!) before I wrote my memoir, A Girl Called Tim.

I waited until I was almost 60 (a grandmother!) before I wrote my memoir, A Girl Called Tim.

I had wanted to write my story for more than 30 years and suddenly the time was right.

The answer as to why I waited so long is found in my childhood.

I developed anorexia nervosa shortly after my 11th birthday, in 1962. The illness was unheard of in the rural region where I was growing up – a dairy farming district in Gippsland, a beautiful region the southeast corner of Australia.

My mindset then was the same as that experienced by children with the illness today. The creepy thing about anorexia nervosa is that, initially at least, the sufferer is not aware the thoughts and feelings belong to the illness and not them.

At age 11, my family home was not connected to electricity – we had a wood stove and used kerosene lamps for lighting; I carried a candle to bed. My primary education took place at a one-room school of 24 children, and our family farm was 12km from the nearest small town. My world revolved around riding my bike, horse riding, swimming, reading books and happily helping my parents to look after the cows, calves and chickens. There were no glossy magazines or suggestive television shows to influence my thinking.

Memories of this time, when most of my thoughts suddenly became no longer my own, remain crystal clear. My parents and my sister, who was several years older than me, seemed unable to comprehend that I had an illness. My parents took me to one doctor, when I was 12, who advised them that I did ‘not want to grow up’ but that was the limit of any explanation. At this time there was a lack of awareness not only about anorexia but also about mental illness. The reason I did not want to grow up was because I wanted to be a boy.

I changed from being a sunny, bubbly-natured child to being increasingly selfish, self-centred, stubborn, withdrawn, moody and inflexible. My mother was embarrassed by my emaciation and by my insistence of running everywhere. In the countryside, there was no place to hide and she was constantly saying: “what will the neighbours think?”

Unable to understand that my anxiety or depression was part of an illness or that my self-absorption was due to fighting a battle within, my mother pleaded: “Why can’t you be like other girls in our district?” I wanted to be like them but didn’t know how; I didn’t know that I was suffering an illness. If I tried to explain I was told I had too much time to think, that I should ‘pull up’ my socks – in other words, get on with life. My sister, exasperated with my behaviour one day, said: “You have Satan within you.”

On entering my teenage years, my untreated anorexia transitioned into bulimia. In many ways, my life became one big torment. I looked ‘normal’ but within my mind I was living two lives: one internally with my eating disorder and the other with the outside world.

Literature and writing were my ‘escapes’. A cousin gave me a diary for Christmas when I was 11 years old and I have kept one ever since. My diaries were my biggest resource in writing my memoir.

At times during my long illness my diary doubled as my only friend, a confidante, a place where I poured out my thoughts in an effort to make sense of them. At 18 I began a career in newspaper journalism, and when I married a farmer at 20, three of us walked down the aisle – my husband, my eating disorder and myself. I tried to be “normal” but my torment grew. My illness continued to gnaw holes in my mind and my soul.

By my mid-twenties, although working full-time, studying by correspondence and being a Sunday School teacher, I feared I was going crazy and would be locked up and separated from my husband and four beautiful little children. I strove to keep myself busy to try and escape the constant emptiness within. It didn’t work. Death seemed the only way out but my love for my children gave me strength to confide in a family doctor. By now my illness had been untreated for 17 years. For the next five years, I was misdiagnosed; I was 33 when referred to a Melbourne psychiatrist who understood my illness and my struggle.

My undiagnosed anorexia and bulimia had set me on a roller-coaster path of chronic depression and anxiety, self-harm and broken relationships. I was often sustained by the thought that ‘I must get through this. I must, and when I do, I will write a book so that others do not feel so alone or suffer for so long.”

The journey of recovery took a long time. I’d lost my family and had almost lost myself. The pathway was treacherous, filled with crevices and potholes. For years, I seemed to fall into each and every one – I’d slip into a depression and take months to haul myself out. Without my family’s acknowledgment that I was really an ‘okay’ person, worthy of their love and approval, I floundered about, unable to find a firm foothold on which to rebuild my sense of self. The little girl of 11 remained in my troubled mind and body but needed help to escape from the prison of my illness.

Months turned into years, and years into decades. I lived for the day when I could shout to the world: “I have recovered my soul! I have peace in my heart and my mind!”

At 55, I was free to do this. I’d got myself back!

June with her eldest grandson.

A complete ‘cure’ is not possible for me, but I am ‘recovered’. More than 20 years of ongoing therapy, together with the love of family and friends, have helped me re-discover myself, improve my quality of life, and set me free. To be at peace within my mind, after more than 40 years, is a continuing joy that words cannot adequately describe.

Five years ago I resigned from my position as a newspaper editor to climb what I called my ‘literary Everest’. At 55, after decades in ‘training’, I was ready: strong enough and resilient enough, to expose my anorexic-bulimic tormentor, in the only way I knew how: with words. I was ready to share my story, with the wish that other children who developed an eating disorder would receive treatment quickly and that adults would be heartened to know that there is hope at every age.

While researching for my memoir I learnt about Family-Based Treatment, also known as the Maudsley Approach and thought: “this is the answer! This is what I dreamed of, and yearned for, through my struggle!”

My memoir went on hold while I wrote My Kid Is Back – Empowering Parents to Beat Anorexia Nervosa with Professor Daniel Le Grange, of the University of Chicago, as my collaborator. I didn’t want children to suffer as I did, into their adulthood. I wanted their personalities restored, quickly, surrounded by their family’s love and understanding. I didn’t want their illness to tag along, as mine did, when they left home, entered relationships and embarked on careers. So I wrote about Family-Based Treatment.

My Kid Is Back was released in Australia and New Zealand by Melbourne University Publishing Ltd in 2009 and by Routledge Mental Health in the United Kingdom, Europe and North America in 2010.

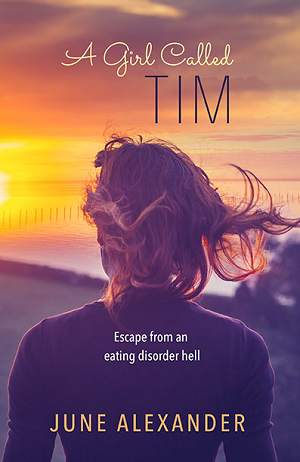

Enriched by fresh insights into the illness that had affected much of my life, I returned to ascending my Everest, completing my memoir, and the result is A Girl Called Tim – Escaping from an Eating Disorder Hell released by New Holland Publishers, Sydney, in February 2011.

Every time I share my story, I find that others share their story in return. Sometimes much courage is required to recall and share painful experiences, but the process of doing so can be like the cleaning of a deep wound. Doing so tenderly and thoroughly, surrounded by compassion and support, allows the pain of such experiences to abate and heal. Liberation is the reward. This is far preferable to living in denial and running the risk that unattended, painful experiences may fester and implode, causing torment and much despair.

The airing of each story, the release of each emotion, enables the rich tapestry of life to grow stronger and its threads to shine more brightly.