An Enduring Relationship: the Patient and the Therapist Who Does Not Give Up

An Enduring Relationship: the Patient and the Therapist Who Does Not Give Up

I was thirty-two, suicidal, and trapped in a self-destruction spiral when I met the psychiatrist who would save my life. I had developed anorexia nervosa at age eleven and the illness was embedded in my brain. ‘Prof’, as I called him, won my trust, saved my life. My therapy had no name. What mattered was the psychiatrist-patient relationship. Prof believed in me and I believed in him and this made all the difference. Our therapeutic relationship began in 1984.

I was thirty-two, suicidal, and trapped in a self-destruction spiral when I met the psychiatrist who would save my life. I had developed anorexia nervosa at age eleven and the illness was embedded in my brain. ‘Prof’, as I called him, won my trust, saved my life. My therapy had no name. What mattered was the psychiatrist-patient relationship. Prof believed in me and I believed in him and this made all the difference. Our therapeutic relationship began in 1984.

Prior to meeting Prof, I worried he would conclude there was nothing wrong and confirm I was an incredibly inadequate person. Other doctors had tried their best but, through misdiagnosis, my struggles had got worse. More than two decades had passed since I developed anorexia.

I had received no professional help during this time. I had survived by transitioning into anorexia-bulimia. Prof asked me to fill out a lengthy life history.

I described my childhood which included early identity confusion (e.g. my mother called me Tim when good, Toby when bad); and how puberty onset at 11 sparked intense anxiety and anorexia nervosa, leading to self-harming, and disconnection of body from self.

Many of the effects of starvation on my body in childhood diminished when adequate nutrition resumed in my mid teens. However, some effects of prolonged malnutrition on my brain continued into adulthood.

I was ready to conclude I was a hopeless case. However, within minutes of meeting ‘Prof’, I knew he could help me. He ‘saw’ me, beyond the layers of the eating disorder, and confirmed an illness in my brain. I definitely, immediately, felt relieved. I was not simply weak-willed after all and perhaps, with the right help, I could heal. However, beyond the initial euphoric moment, fear swept back in.

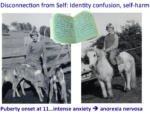

‘You have never been helped since developing anorexia,’ Prof said matter-of-factly. He suggested my private diaries, kept since the illness developed, might help to sort my problems.

You’re not to give up hope

At my second appointment, Prof provided the first accurate assessment of my illness. He confirmed I had developed anorexia nervosa, transitioning from restrictive type to binge/purge, and described my level of functioning as ‘fair’. He observed: ‘Your life has been full of anxiety and depression.’ ‘You are a ‘chronic case’.’ There was no quick fix. The enormity of this struggle hit me as I left Prof’s consulting room that second day, clutching a prescription, the first of many over the next several decades. However, on my next visit, Prof said:

You’re not to give up hope. You’ve had the illness more than 20 years and it will take time to get well.

I told Prof how I had four children in four years, each pregnancy becoming a desperate bid to suppress the eating disorder, and how, at age 28, and suicidal, I was driven to share my inner struggle with doctor for first time.

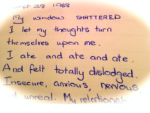

Acknowledging that thoughts and behaviours, which for decades had seemed helpful, if not absolutely essential for survival, must be jettisoned because they are harmful, was beyond scary. How could I face the challenge of accepting that my structure of self, to which I had devoted and sacrificed many hours of each day, since childhood, was false and deceptive? That my thoughts were not authentic? That instead, these thoughts were symptomatic of a brain-based disorder? Who was I????

Getting ‘me’ back

Prof was leader of a small team in whom I developed trust. He set about helping me unearth and confront the layers of illness—interlaced with secrets and shame—that were suppressing the true me. Visits to Prof took on a pattern.

I would arrive with pages of notes. He would read my ramblings, look at me, ask questions, offer guidance, and check prescriptions. He believed in pharmacological solutions. The medications slowed my illness thoughts, allowing time for the gradual restoration of self-belief, chiefly through the method of written communication. Prof understood that I felt safer writing what I didn’t yet feel able to voice.

In this way, my personal diary provided a conduit through which we built a trusting relationship, a vital first step in reconnecting with self.

The path was not always rosy. Interpersonal relationships had suffered throughout my illness and continued to do so. My complete family of origin and my marriage were lost, but my life was saved.

Going forward required a total re-make; a reintegration of various frayed or lost strands of the true ‘me’.

Besides overcoming fear that accompanied regular eating, I faced the mammoth task of locating and re-integrating fragments of self into a sound foundation, from which to venture forth and re-engage in life. I had to let go thoughts, behaviours, and relationships that fed my illness, and develop healthy thoughts and behaviours.

Post divorce, I became drawn into unhealthy and chaotic situations and relationships. The eating disorder bully had been part of my life for so long that being kind to myself and keeping myself safe seemed foreign. Consequently, when starting to feel settled, I would seek fresh and familiar sources of chaos that aligned with the eating disorder traits. Prof would patiently offer encouragement:

It is not that you are wrong but that (solution or person) is not right for you; keep trying.

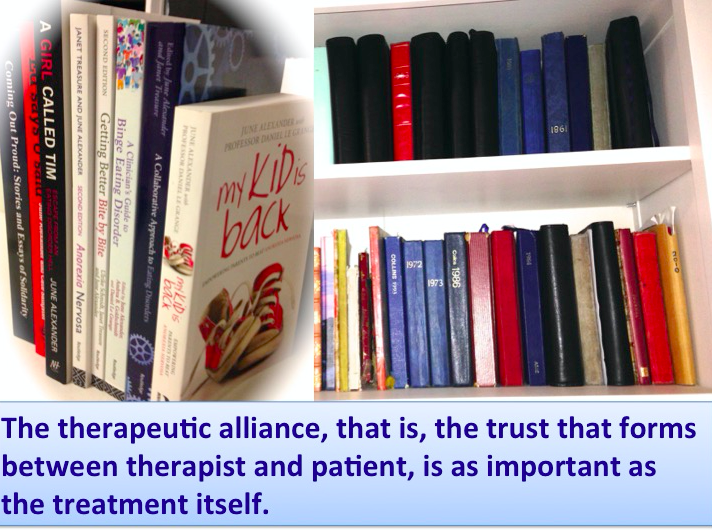

The therapeutic alliance – bridges of trust

The authentic me slowly learned how my decisions, sometimes in the name of staying “in control” and being “good,” were maintaining my illness. To be free, I had to develop a new approach. Drawing on my diaries in writing letters to Prof helped me to edge forward in recovery.

From this tenuous leap of faith in the direction of Prof, I began slowly to trust and connect with true ‘me’. With encouragement, I began to read through earlier diaries and reflect on them. This involved re-visiting painful and traumatic times. Addressing layers of suppressed emotion was a prerequisite for escaping the eating disorder’s grip and constructing a safe base of self-belief. As well, on-going physical health issues needed to be addressed.

Prof knew that he could only do so much: to be free I had to reach the point where I could transform my belief and trust in him to belief and trust in myself.

2006 was the first year in more than four decades not dominated by my eating disorder. I was eating regular and nutritious meals, no longer slipped into deep depression and was learning to manage residual anxiety.

Able to function and engage more in the mainstream, Prof encouraged the writing of my memoir, A Girl Called Tim, released in 2011.

What mattered most during my treatment with Prof was not the treatment so much but the level of trust formed between therapist and patient. Just knowing he was there, was helpful. He was an anchor, a safe person with whom to share the inner hell that I had lived with alone for decades; and he became the sounding board for the emerging authentic self.

He patiently taught me techniques to strengthen authentic thoughts. If feeling confused, or confronting a problem, today I automatically think ‘Action beats anxiety’and, in decision-making, I ask, ‘What is in my best interest?’ If feeling unworthy, or experiencing self-doubt, I remind myself to stand tall and own my space, for ‘I deserve to be treated with respect’.

Accepting that ‘life is not fair’ is liberating

I had been expecting life to be fair; indeed, often doggedly insisting it “should be”. It wasn’t. It took time to appreciate Prof’s understanding that my getting hung up on an issue, because it ‘wasn’t fair’, or clinging to a relationship that was unhealthy for me, served only to strengthen the eating disorder’s hold, giving it yet another ‘reason’ for me to binge or restrict, or engage in other self-harming behaviours. When I pushed aside the eating disorder’s interpretation, and absorbed the meaning behind Prof’s words, inner healing took another step forward.

Somewhere along the way I said to Prof: ‘I’ve got my life picture sorted now’. He said: ‘No, you haven’t’. Again, he was right. I know now that life is like a never-ending jigsaw.

New pieces continue to appear, requiring adjustments to the picture in an ever-enriching and healing way, as long as life itself. Thank you, Prof, for not giving up on me.

In the ten years since reconnecting with true self, I have written nine books on eating disorders. They include my memoir A Girl Called Tim, and latest book, Using Writing as a Therapy for Eating Disorders – The Diary Healerwhich is the creative work in a PhD in Creative Writing with CQU Australia; I also contribute a chapter from the patient’s perspective in ground-breaking book Managing Severe and Enduring Anorexia Nervosa.

- This exploration of an enduring physician-patient relationship is a tribute to the late Professor of Psychiatry, Graham Burrows AO. Prof Burrows died in January 2016, aged 77. Prominent in Australian and international psychiatry, he was my psychiatrist for 30 years.

- This article is an edited version of the paper, An Enduring Relationship: the Patient and the Therapist Who Does Not Give Up, co-presented with Professor Stephen Touyz at the 14th annual conference of the Australian and New Zealand Academy for Eating Disorders, Christchurch, New Zealand, on August 26, 2016.