My diaries have a new home in the National Library of Australia

Inseparable for more than 60 years, our shared life will continue

My diaries have a new home in the National Library of Australia

My eating disorder has gone to Canberra, Australia’s national capital.

The eating disorder has travelled there within the pages of my diary collection, acquired by the National Library of Australia (NLA). There, the eating disorder will be open to public scrutiny.

Canberra is an eight-hour road journey from where I live. My diaries and I have never been so far apart, but we both feel at peace.

A prime factor in making my private diaries public has been the National Library curator’s comment that making my diaries available through the Library’s collection can help progress important work, especially increasing awareness and understanding of eating disorders and encouraging the development of better treatments for sufferers.

When I developed anorexia as a little girl living in rural Australia, very little was known about this illness. Now, I am a grandmother, and anorexia remains one of the most severe and complex mental illnesses of our time to understand and treat.

Shining a light in the crevices of a complex illness

The anorexia that pervades the opening pages of my first diary at age 11 becomes entwined in the diaries for decades. It wreaks havoc on my life. The diaries are a testament to the struggle to regain a mind sabotaged in childhood by anorexia. In adulthood, the diaries document efforts to reconnect with a healthy self buried by the eating disorder. Eventually, I do find myself. The diaries record this.

Having lived with an eating disorder since childhood, “recovery” is not a valid or appropriate word to describe my experience. I will never know what kind of person I would have become or what life I would have lived if I had not developed anorexia.

The terms “ongoing healing” and “self-discovery” are more meaningful.

I cannot pretend to erase the experience of the eating disorder. It shaped and influenced every day of my life for decades. I eventually broke its powerful grip. Today, my healthy self is the boss. My eating disorder is relegated to the back blocks of my mind, where it has no rights and is silenced.

I look upon this sundown period as one where I feel guarded compassion for my eating disorder – in my early years, it developed as a coping tool for a very anxious little girl. Years later, when my life was hanging by a thread, I would learn the harsh truth that this way of coping was deadly and self-harming. By then, the illness traits were too embedded to be eradicated. Instead, with patient guidance from health professionals over many years, I learnt to trust their voice more than my eating disorder’s powerful ‘voice’; I slipped and slid a lot; I tried and failed repeatedly to find my own voice.

Rebuilding a healthy self

The truth that the eating disorder’s way would always fail was scary to accept; acceptance involved letting go of the only identity I knew and establishing a healthy self. I had to learn, through trial and error, who I was without the eating disorder. New thoughts had to be developed and practised until they over-rode the illness thoughts. My diaries record this fraught and bumpy time. Out of belated developmental experimentation, healthy thoughts and coping skills gradually emerged, with my diary a practice ground for this self-restoration work.

In my mid-fifties, I achieved the milestone of restoring more than half of my healthy self. Self-healing accelerated after that, and, for the first time, I publicly shared the intensely private battle I’d been waging within myself since childhood.

The diaries provided a rich repository of experiences on which to draw in advocating greater awareness and support for people who develop an eating disorder. They became a major resource for writing my memoir, A Girl Called Tim. They inspired my PhD, which I undertook in my sixties and led to the publication of the book Using Writing as a Therapy for Eating Disorders.

My diaries have found a public role in these ways and more. They have validated my experience and have assisted in turning the tables on the illness that thrives on secrecy, shame and stigma and wants to isolate and conquer those in whom it develops. This is penance time for the eating disorder. I’ve long believed that anorexia cannot survive in the light. Exposing it by talking about it, researching it, and reading stories of lived experience help to reduce its power. In the National Library, it cannot hide.

The journey

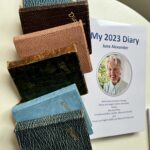

Through the years: My first six diaries, 1963 to 1968 and the 2023 diary, now digitised.

My first diary was a Christmas gift when I was 11 in 1962. It allowed one day to a page, starting on January 1, 1963. I was so excited to hug and hold this little soft-covered new friend that I wanted to write in it immediately. I didn’t want to wait six days. So, I wrote on the few plain memorandum pages at the back of the diary.

I didn’t know it, but I had already been in the throes of anorexia for almost a year, and the diary immediately presented itself as a friend and a safe place to connect.

I didn’t know it then, but the diary would help save my life and sanity. Over the next 60-plus years, it would, in turn, serve as a coping and survival tool, a self-growth and self-healing tool, and a self-maintenance tool. It would help me to develop new, healthy thoughts and regain my identity, which the anorexia had ravaged. For many years, I did not know who I was – I did not know if a thought was authentic, or if it belonged to my eating disorder, or was propelled by doses of prescription drugs. Thank you, my diary family, for helping me find myself.

Fast forward to 2023. I was updating my will and getting my papers in order. I wondered, “What arrangement can I make to care for my diaries when I’m no longer here?”

I wondered if the State or National Library might be interested and decided to approach the National Library of Australia first. I was amazed at the response.

I had inquired if the NLA would be interested in caring for my diary collection upon my death.

The senior curator of the National Library wrote:

Your collection of diaries sounds remarkable in many ways. The span of time they cover is impressive, and we feel that your experiences of growing up in rural Australia, being a working mother, and most especially, your battle with an eating disorder are worth preserving in the national collection, and we are interested in acquiring them.

I note that in your offer, you specified that you would like to transfer the diaries to the Library upon your death. We wondered if you might be willing to reconsider this and deposit them sooner. The Library is a safe depository for valuable material, preserving it in proper archival conditions and protecting it from environmental threats such as pests, bushfires and floods. We hold a lot of sensitive material—especially in our manuscripts collection—and we offer donors various options to control or restrict access to their material.

I consulted my children and friends, had long conversations with the NLA curator, and decided to proceed. My diaries were handwritten until 2016 when I began writing in digital format.

Completing the Very Special Task of preparing and packing the diaries for their journey to Canberra this past week has been a massive step in the shared life of my diaries and me. I wasn’t sure how I would feel, but I am happy rather than sad and relieved rather than worried. The fact that we are being separated is not the end of our relationship. My diary, like a daily serial (one never knows what the next day will bring), will continue to add a new page each day for as long as I live.

Making the diaries available to the public

Saying ‘goodbye’ to my diaries as they depart for their new home in the National Library of Australia

I am grateful to the NLA curator and her colleagues for offering my diaries a safe home where they can be a resource for others.

I have agreed with the Library’s preference for making the diaries available to the public now rather than waiting until I die. I have also followed the curator’s suggestion, restricting some diaries for a certain period, and I have written a cover letter to give readers the contextual information I want to convey. This letter will be included with both the restricted and the non-restricted diaries. As for the restricted diaries that require my permission – when a reader requests to look at that material, the Library will let them know that they can only look at it if they have my consent. At this point, my email address will be supplied. Then, it will be up to the reader to get in touch with me, and I’ll be able to talk with them to ascertain if I feel comfortable with them accessing the material.

As manuscript material, my collection (both the restricted and non-restricted parts) will only be delivered through the National Library’s Special Collections Reading Room, a specialised space with a higher level of staff monitoring to ensure that material is being used appropriately.

With these arrangements, I feel comfortable and confident about depositing my diary family into the Library’s collection. My diaries will be accessible later this year.

This is my letter that will greet prospective readers:

Dear Reader,

As you embark on the journey through the pages of my life, documented diligently from age 11, I extend a warm welcome and a word of guidance. This collection, spanning more than six decades, is an intimate chronicle of my personal experiences, observations, and the evolution of my thoughts and feelings through my life’s myriad stages and struggles.

The contents of these diaries are deeply personal. They represent my perspective alone and are a reflection of my journey. The people mentioned within these pages, including my children and others who have crossed paths with me, are viewed through my lens, influenced by my interpretations and emotions at the time of writing.

This collection is not an attempt to speak for others or to present a comprehensive narrative of any life but my own. The observations and sentiments recorded are subjective and should be considered as such. My account may differ significantly from the perspectives of those who have shared parts of this journey with me. Their views, experiences, and truths may diverge from what has been documented in these entries.

I offer my life’s collection to you as a study of an individual’s existence across the changing landscapes of time, society, mental illness, and personal growth. These diaries are a testament to the human experience—my experience—with all its complexities, joys, challenges, and revelations.

As you delve into these pages, I invite you to explore the events and reflections recorded and the broader themes they may suggest about life, change, and human resilience. My diary collection will serve as a valuable first-person, lived-experience resource for understanding the nuances of personal history and the diversity of human experience.

I appreciate your interest in my diaries. May you find in them insights, inspiration, or whatever it is you seek in the intricate tapestry of a life lived and recorded.

Warmest regards,

June Alexander

Knowing that when the final diary entry is penned, my diary family will be kept safe in the National Library of Australia for others to access and research fills me with a sense of peace, meaning, and gratitude.

Meanwhile, my immediate plan is to focus on completing two eating disorder book manuscripts: My Kid is Back, Second Edition (about Family Based Treatment), with Prof. Daniel Le Grange, and a book explaining Multi-Family Therapy, with co-author Prof. Ivan Eisler. My role in each of these books is to collaborate with the researchers and be a voice for the families who describe their experience of these evidence-based treatments.

When these manuscripts are submitted to Routledge (London) later this year, I will celebrate with a trip to Canberra (with as many family members as possible) to meet the curator at the National Library and visit my diaries in their new home.

I will hold and hug my little first diary. I will remember that little girl diarist who found refuge in her writing. I will grieve for her losses and admire the courage she showed on the long and winding journey that her life would take. I will be grateful that she never gave up. I will hug my first little diary close to my heart and tell that little girl, “You are safe now. You are safe.”

Safe from the eating disorder, and safe in our country’s National Library.

Share your story

My posts will be spasmodic for the next few months while I complete two manuscripts. I invite guest contributors — I especially encourage you to share how writing has been helpful to you – get in touch by filling out the below form.