Korea’s EDAW 2024 puts epistemic justice on the table

Continuing the struggle to improve women’s standing

Korea’s EDAW 2024 puts epistemic justice on the table

So, I quit my job again at the end of January. The healthcare company I worked for was one of those doctor-owned ventures not uncommon in Seoul, South Korea, where medical doctors generally belong to the highest income groups and are probably the most exclusive interest group. In a misogynistic society, the most significant issue in those companies might be their culture mirroring a feudalistic hierarchy with male doctors at the top and female nurses beneath them. As anticipated, I wasn’t adequately credited for my contributions despite doing much more and higher-level work than my male coworkers.

I had tried and entered several negotiations with the doctorpreneur CEO himself. On the last occasion, he suggested I get a promotion to be called a director rather than a general manager. I agreed, as aloofly as I could, suppressing my chronically low self-esteem. But he betrayed me at the company-wide kick-off meeting for the new year. The executive director, the military mate and college alumnus of the CEO led the meeting. At the end, he called me and a colleague sitting beside me to stand. Making us stand among everyone, he continued talking:

These two individuals will be called ‘directors’ from now on, but there will be neither a pay rise nor changes to their name cards. (Their new title) is just to imply they should take on more responsibilities and work harder for the company.”

Everyone booed and laughed, but I couldn’t laugh at all.

Frustrations of inequality rankle

Months ago, several male coworkers were promoted to directors at another company-wide workshop hosted at a hotel conference hall. This was a formal ceremony where the executive director presented each of them with proper certificates of appointment. The men were recognised for their authority, but we women workers received no recognition.

It wasn’t a surprise. Once the company shared the outsourced brief analysis via group chat, I opened the two-pager out of pure curiosity, but it ruined my mood because of its shameless description. It reported that the company’s female workers comprised less than 30 per cent of the workforce and were paid less than 60 per cent than their male counterparts. However, it claimed these statistics were relatively favourable compared to the whole industry. My frustration was so enormous that I had difficulty sticking to that day’s work.

I submitted my resignation letter, deciding I couldn’t waste my time and efforts on this company. Ironically, two male workers demoted from their prior positions remained at work despite the demotion being a clear message of the company’s urge to resign. When I talked about this to my psychiatrist, he suggested that the unashamed two might be more realistic and clever than me. I understood what he meant but still think he couldn’t appreciate what I had given up, but my male counterparts wouldn’t need to do so.

Whirlwind of Preparing the Second EDAW

On the other hand, I felt great relief quitting my day job. I was still the single agent in charge of Korea’s EDAW, and the cumulative workload had been enormous. Before quitting, I would arrive at work at 6:20am and leave at 4pm. Afterwards, I would meet people and arrange things for the EDAW preparation before going home. I met so many people that I had difficulty recalling whom I had talked to and when, while remembering vividly the topics I had talked about.

After two days of hibernation, I restarted my work for the EDAW. The posters were out, all seven sessions for the seven days were set, and several publicity projects awaited me. I had lots to write on my table. The hardest part was that we failed to secure corporate sponsorship this time, but I opened our bank account for free crowdfunding in case of need and kept trying to attain sponsorships.

To provide a brief overview of our second EDAW sessions with ‘Epistemic Justice’ as their spine, the first day, February 28, will start with the lived/living experiences session, as in the first EDAW. This time, we will have eight speakers, including me as moderator. I jokingly say that this time, we are ready.

On the next day, February 29, three brave mothers who have supported their daughters struggling with eating disorders will join the audience:

- Ms Sangok Park, Chaeyoung’s mother, appeared with her daughter in the indie documentary film about Chaeyoung’s eating disorder and the mother-daughter relationship, A Table for Two.

- Ms Jihye Lim is a practicing endocrinologist who had to care for her teenage daughter alone because there were no eating disorder specialists in the metropolitan city where she lived.

- Ms Younghee Park is Sunmin’s mother, who recently became a grandmother when Sunmin gave birth to a baby boy.

On March 1, Professor Eunkyoung Choe, a human-computer interaction researcher at the University of Maryland, will join us to discuss digital healthcare.

The next day, March 2, three experts with distinct perspectives will discuss the healthcare system in Korea:

- Dr Saerom Kim, MD, is a health policy researcher;

- Professor Hyuna Kim is a renowned rheumatologist and author of health system criticism, including The Era of Medicine As Business and a personal memoir about caring for her troubled daughter titled One Day My Daughter Collapsed into the Abyss Silently; and

- Ms Juran Ahn is a psychiatric nurse with more than 30 years of experience and a meal support therapist in eating disorders treatment.

In an email to these experts, I asked why the government established no other than the National Tobacco Control Centre (NTCC) within the Korea Health Promotion Institute about 10 years ago, notably when the corrupt right-wing regime raised tobacco prices. Moreover, the budget for the newly minted organisation reportedly comprised only 3 per cent of the tax from raising the tobacco price. The NTCC covers every aspect of work that I envision for a potential national centre for eating disorders, except for the sickening TV ads. Recently, they broadcast TV ads depicting two kids secretly calling the NTCC to seek help for their father or grandparents secretly calling to help their granddaughter quit smoking, framing it as a ‘disease.’

On Sunday, March 3, our singer-songwriter, Barbara, and Chaeyoung will host a concert. Chaeyoung will read quotes from her favourite books, including her recently published memoir, This is Also a Part of My Life. The following day, the fierce art critic Rita and I will discuss auto-theory and the ethics of writing a memoir. On the final day, March 5, our beloved feminist godmother, Dr Heejin Jeong, will deliver a lecture.

The Lived-Experience Witnesses

In conjunction with our EDAW 2024, Chaeyoung, Eunah, Seokyoung, and I gathered at a rented studio in Gangnam, Seoul, on January 21 to film a short interview. Chaeyoung, Eunah, and I had all experienced life at now-extinct eating disorder inpatient hospitals, and we decided to discuss it. Fortunately, the filmmaker Seokyoung graciously agreed to help us.

Eunah is the eldest among us. Born in 1975, she attended almost all the first batch of eating disorder clinics that started to open in the mid-1990s in Seoul. Five years younger than her, I was the first patient at the first eating disorder inpatient hospital, opened in November 2001, and Eunah was admitted there in 2003 before being moved to another inpatient hospital. The youngest of us, Chaeyoung, born in 1993, was admitted to another eating disorder inpatient program by her single mother when she was just 15 years old.

Except for Chaeyoung, who had been hospitalised at the average psychiatric inpatient ward in a general hospital where the eating disorder patients, among others, should have gathered at a special table every mealtime – and surprisingly, the plates of each patient had posts of different calories prescribed to them – the two hospitals where Eunah and I were hospitalised were staffed by private psychiatrists. The one where I was the first patient, and Eunah had been re-hospitalized in 2003 was already closed and forgotten when Chaeyoung’s mother sought hospitals for her young daughter in 2007.

We talked and filmed the whole discussion and started to post clips from the recording on our Rabbits in Submarines Collective Instagram account. I made the title for the project, If You are Still Alive, Answer Us. As you would expect, this is a shoutout to our old alums of the inpatient wards.

The memoir of the British journalist Hadley Freeman, Good Girls, was recently translated and published in Korea. The publisher sent a copy, and I devoured the entire volume on subway trains and at a cafe that day to write a review to publish as early as possible. I contributed my long article to the Mindpost, and I conclude with this lamentation:

What I’m curious about is this. Is the boom in opening clinics right after the division of medicine in 2000 related to the opening of inpatient eating disorder wards around that time? The people who actually worked with patients 24 hours a day in the inpatient ward were second-shift nurses on a low wage who had not received specialised training in eating disorder treatment. Was that treatment system appropriate? What kind of economic rationale was behind the creation of those hospitalisation facilities for eating disorders, the neglected category that was not covered by insurance, not only for any treatment but also for simple paper-and-pencil tests for diagnosis until now, 20 years later? Why was it accepted as a reasonable business model? And now? Now that the prevalence of eating disorders has become so dire, why is there no discussion on how to deal with it? What is it that makes us a being that is okay to be abandoned?

Ignoring lived experience as evidence is a form of ‘epistemic injustice’

This is my update regarding our EDAW project. Today, while negotiating the draft written by Eunah and already revised several times by me with the editor of Ohmynews over the phone, I pointed out that her request for ‘objective evidence to the author’s arguments’ constituted a form of ‘epistemic injustice’ especially since she had never made such demands regarding Ms Juran Ahn’s upcoming article. I wanted Eunah to vividly describe her experiences as a witness in those forgotten inpatient wards. However, the editor-in-charge said that they couldn’t ascertain whether such recounting of age-old stories would benefit readers, and they couldn’t lend authority to an individual’s report of past malpractices without evidence recognised as proper by other relevant parties.

This is my update regarding our EDAW project. Today, while negotiating the draft written by Eunah and already revised several times by me with the editor of Ohmynews over the phone, I pointed out that her request for ‘objective evidence to the author’s arguments’ constituted a form of ‘epistemic injustice’ especially since she had never made such demands regarding Ms Juran Ahn’s upcoming article. I wanted Eunah to vividly describe her experiences as a witness in those forgotten inpatient wards. However, the editor-in-charge said that they couldn’t ascertain whether such recounting of age-old stories would benefit readers, and they couldn’t lend authority to an individual’s report of past malpractices without evidence recognised as proper by other relevant parties.

Consequently, we have to abandon our idea of publishing Eunah’s memories on the platform. Meanwhile, Ohmynews has accepted Ms Ahn’s description in her article, stating that eating disorder patients relate well to and even support each other but remain wary and distant from therapists, who are seen as outsiders within their close-knit, homogeneous community.

- More information: https://www.instagram.com/rabbitsubmarinecol/ is a hub for everything related to the EDAW.

- Banner caption: The three women in the banner picture are, from left to right: Chaeyoung, Eunah, and Jeannie at a rented studio in Gangnam, Seoul, on January 21. All three women spent time in the now-forgotten eating disorder inpatient wards that existed in Korea during the early to mid-2000s.

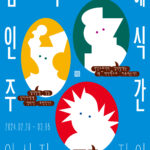

- Poster caption: Korea’s second EDAW will be held from Feb. 28 to Mar. 5. The large letters around the edges read “EDAW – Epistemic Justice.” The small letters in seemingly speech bubbles under the three characters are (clockwise from green one): “Why does the phenomena of eating disorders never cease to exist throughout history?”, “Why isn’t the pathology of eating disorders fixed but rather changes fervently?” and “What is justice for people with lived/living experience of eating disorders?”. Written by Jeannie Park and designed by Euddeum Yang (https://yangeuddeum.com/).