My friend the diary (part 2)

My friend the diary (part 2)

Using diary writing as a self-help and therapeutic power tool

by June Alexander

Strengthening true self through diary-writing

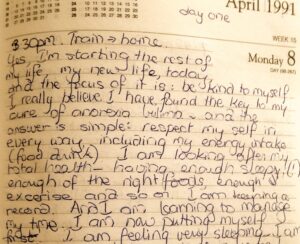

My diary has always been a confidante, but it was not always the friend I thought it was. Sometimes it was a confidante for my eating disorder, recording the illness thoughts instead of my “true thoughts.” At such times, it became a place where rules were made to try and get through each day, and a repository for secrets due to high levels of shame, stigma, anxiety and terror. Recovery required not only a securing and reconnecting of trust within my self and with others, but also within the diary.

During recovery, as I became more aware of the illness thoughts and behaviors, I was able to observe and reflect on how the diary could help to diffuse and avoid the debilitating effects of those illness-driven thoughts and behaviors, for instance, of secret making and self-stigma. This cultivation of self-awareness techniques helped me to see how far I had come in recovery, and to see the illness more in context of my life rather than being my life.

A place to grieve for “life lost” and to explore new thoughts

Importantly, the diary can “grow” with the writer, not only during the early stages of recovery, but also, for example, in the final stages of eating disorder recovery, when grieving becomes an important part of the growth-into-a-hopeful-future process.

My diary reveals grieving for the “life lost” during the illness, and grief in facing the loss of the relationship with the illness itself. The process of recovery involves more than behavioral observations, symptoms reduction, and clinical data and calculations. Recovery is also about emotions and feelings, including grief for the impact of the illness on relationships, and education and career opportunities, and exploration of long-held self-beliefs and emerging new beliefs essential for coping in mainstream. The insight into the effect of grief illustrates the benefits of diary-keeping over time, for the diary can become a resource for self-help and therapeutic reflection.

Even when aware that clinging to a daily regime of weights, calories and exercise routines is playing the eating disorder’s game, severing these behaviors can be scary. There is more healing to do, but when self-reintegration and “true thoughts” become a little stronger than those of the eating disorder, decisions in favor of self and health, and healthy self and body, become easier. I began to use my diary to help accept the illness as part of my life story, and to focus simultaneously on living fully in the “now,” rather than being bogged down in the losses.

Clues in the pages

Through reflection, I slowly learned to recognize how decisions, sometimes in the name of staying “in control” and being “good,” were maintaining my illness. To be free, I had to develop a new approach. Over time, my private diary helped me to recognize the need to seek help when niggling, disruptive, illness-related thoughts began – quickly, for a slip, as simple as eating a chocolate to suppress feeling rejected, could snowball into a relapse. Besides providing a method of communication with my therapist, and remaining a place in which to emote and to confide, my diary became a medium for practicing and exploring new thoughts, and reaching out.

Gradually, I was able to observe the illness experience was of me, but was not “me;” forgiveness became possible, and I could consciously choose to not allow the illness to define me.

How can diary writing disarm an eating disorder “trigger?”

When an eating disorder thought urges you to engage in illness behaviors, grab your diary (whatever form it is – pen and paper or digital) and write. Don’t hesitate. Just write. Write anything. Just write.

The process of picking up your diary and writing, and letting galloping thoughts and feelings flow on and on until they peter out, can help you rationalize your thoughts and see the reality of a situation. In this way, writing can assist in neutralizing and deflecting any pressing eating disorder thought that is pushing you to self-harm.

The benefits of diary-writing as a tool to distinguish your self from your eating disorder can be built on through sharing or reflecting on your writing with trusted others. Taylor, a diarist participant in The Diary Healer, explains:

“Sometimes it would simply be a matter of writing down what ED was saying so I could take this to my treatment team, so they could help me challenge the thoughts. Sometimes it would be a matter of reflecting on something that came up in therapy and realizing how certain ED messages and behaviors were based in inaccurate self-perceptions. Mostly, journaling has been a way to help me and my own voice, more than learning to identify ED’s voice. I needed to find my own voice to achieve and maintain recovery. Journaling through recovery has helped me learn to recognize when something I am mentally hearing or thinking is incongruent with my own voice, values, and way of being in the world.”

The diary can help you to understand the eating disorder “secrets”

Eating disorders form around, and build on, layers of secrets. Your diary can provide a window into these secret thought challenges. For instance, the entries may chronicle your trust in the diary as a friend of self, but when an eating disorder develops, the diary entries may inadvertently assist disintegration of self by listing and emphasizing the eating disorder’s rules and demands. Depending on the stage of your illness, your diary may help to give voice to both authentic thoughts and illness thoughts. Sharing with a trusted therapist, or peer mentor, skilled in the narrative, can help you recognize and confront the illness thoughts.

Entries shared by the 70 diarists in my book The Diary Healer, and PhD research, provided firsthand documentation of daily struggles relating to behaviors, feelings and values that occurred during the disintegration and reintegration of their true self. Some secrets were grounded in childhood and in the earliest days of the eating disorder. For example, with anorexia nervosa, the fear of eating often led to developing an urge to hide food, to avoid criticism, for instance, from one’s mother. Traits of the illness, together with psychosocial influences, encouraged social isolation and secrets not only in the diarist’s home environment but also when an inpatient:

“… A lot of what you feel cannot be talked about in treatment as it may be triggering to others. And sometimes … you feel you’re doing the eating disorder incorrectly or half-heartedly. I worried people would think I was not really sick….”

– Ruby (p. 171-172) The Diary Healer

Write, when talking is too difficult

There is no quick fix in healing from an eating disorder and when misunderstanding, rejection, stigma or shame is experienced, at home, when accessing healthcare, or in the community, reaching out again for support can become doubly hard.

When support is not communicated in a helpful way verbally, writing about it can help.

At home, the sharing of written notes, perhaps left on the dining table, or on the refrigerator door, or anywhere the intended audience will see it, can help to relieve a triggering moment, and responses can be kept for later debrief.

Writing instead of talking can help overcome a tendency to misinterpret what is said or done, at home and in therapeutic situations. The mere process of writing can ease anxiety, provide comfort and be nurturing. In addition, it can put distance between you and the event, and provide an opportunity for reflection. Putting everything in writing and on the table helps to expose the eating disorder, so it has nowhere to hide. Caregivers and therapists can acquire narrative skills to gently confront the illness thoughts, and offer more healthy perspectives, by engaging in writing-sharing during periods of under-nourishment.

Knowledge, love and the diary – a powerful trio

Everyone in the family is affected in some way during the illness experience. With due consideration, the writing process can give permission not only to the diarist but also other family members to grieve, understand, forgive and develop self-love.

Families do not cause an eating disorder. However, the family’s role and involvement in treatment and recovery can be crucial. Knowledge is power and so is love. Love is a powerful healing tool when expressed in a way that meets the needs of the person with the illness, and reduces the pull of the eating disorder.

I am ever-grateful to my diary, family, and treatment team, for helping me to survive, cope and heal from my illness so that I can be free today to explore who “I” am in the fullness of life.

Making a date with your diary is time well spent. Consider it an investment in “true you.” Writing a daily episode of your own life story is the best investment you will ever make!

Write!

About June

June is a writer and international award-winning advocate in the field of eating disorders. She developed anorexia nervosa at age eleven in 1962, an illness that has largely shaped her life.

Since her recovery in 2006, June has written nine books on eating disorders. Her latest title, Using Writing as a Therapy for Eating Disorders—The Diary Healer, is the main work in her Ph.D. in Creative Writing.

June’s passion for the narrative and patient-centred care has led to involvement in eating disorder advocacy at local, national and international levels. She works as a life writing and wellness skills mentor for patients, caregivers and health professionals. For more details see June’s website: https://lifestoriesdiary.com.

Recently, June has also engaged in an international exchange with Sandra Zodiaco and the Italian Association “Mi Nutro Di Vita” (Genoa), fighting against Eating Disorders and the stigma surrounding these illnesses. As part of this cooperation overseas, the Italian translation of this article by June is available at: www.minutrodivitalilla.blogspot.it.