Is your diary your friend or foe?

Is your diary your friend or foe?

by June Alexander

The basic elements of writing as a tool for record keeping, nurturing, healing, reflection, creativity and spiritual discipline have been the essence of diary keeping for centuries. However, special considerations apply for the diarist who has an eating disorder.

Historically, diaries have been regarded as a deeply personal, private and confidential document. The word ‘diary’ originates from the late 16th century, from Latin diarium, and the earliest known surviving diaries in the English-speaking world date from this time. Before then, the word diarium was used only for describing a person’s daily allocation of food. I found this background interesting, if not ironic, in my PhD study* of the diary’s role in the development of, and recovery from, an eating disorder. For decades, food had been the bane of my life. As a diarist over many years, the recent realization that my diary (which can also be called a journal, log or blog) had at times been a foe, even when I believed it was a friend, became the catalyst for my research.

Disconnection between body and self

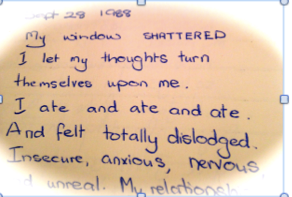

When an eating disorder develops, symptoms manifest around food. A common experience is for disconnection to occur between body and self. The extent is evidenced in thoughts, feelings and behaviors as the affected person progressively loses touch with, and becomes separated from, their authentic self, and engages in acts of self-harm rather than self-love. My diaries bulge with documentation of this behavior.

The role of diary writing in this disintegration and reintegration process of self and body is explored in my book Using Writing as a Therapy for Eating Disorders — The Diary Healer. Through diary excerpts from more than 70 participants, I look at the use of diary writing in patient-centered healing and present new perspectives in a field yet to find causes and achieve consensus on solutions to overcoming the complex challenges inherent in an eating disorder.

A survival tool

At age 11, the same year I developed Anorexia Nervosa, I received a diary as a gift. It marked the start of a literary journey in which the diary would record the loss and recovery of self, and serve as a survival tool in both destructive and constructive ways.

Forty years would pass before recovery would enable me to be an observer as well as participant of my experience and see how the diary had aligned with, and fed, my eating disorder.

The rule about rules

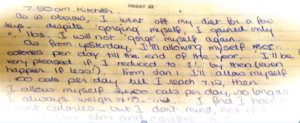

I know, now, there are only two things to remember in diary keeping: firstly, date each entry, and secondly, make no rules. I knew the first rule but the second one eluded me. When you have an eating disorder, rules dominate every day but they can be counter-productive. By age 19, pages of my diary were filling up with rules to live by.

An eating disorder infiltrates thoughts and behavioral habits under the guise of helping to ease anxiety, control desires and manage self. It fools you into thinking it can help you be the person you want to be. It thrives on privacy—on a relationship with you alone—and encourages secrets.

As a young woman, the diary presented to me as a safe place in which to sort thoughts, ease confusion; practice self-control.

But …

Confiding in the diary was also strengthening the eating disorder, where bossy demands became increasingly impossible to meet. When rules were inevitably broken, another punishing diet and exercise regime took their place. Nothing was ever enough.

Losing my self

By age 28, my diary recorded almost complete loss of self.

Outwardly, I presented as a wife, mother, journalist, sister and daughter but within, the diary reveals a different story: of daily lists and pledges reflecting a desperate bid to stay sane and escape constant mental torment. A good day depended on strict adherence to my carefully crafted rules, set down in the diary. For instance, having to:

- weigh this many kgs

- run this many kms

- eat no more calories than this, and a never-ending list of

- doing this, this and this

A healing tool

Suicidal, and fearing a diagnosis of madness, I mustered the courage to share the burden of my secret struggle with a doctor for the first time. The illness was so embedded that years of misdiagnosis followed. Neither doctors nor I were aware the diary was helping to keep me a prisoner of the eating disorder.

A breakthrough came in my 30’s, when a psychiatrist saw “me” beyond the entrenched layers of illness, and gained my trust. Understanding the value of narrative medicine, he listened and encouraged written communication. My trust in the diary became a tool with which to establish a trusting relationship, a vital first step in reconnecting with, and trusting, self.

Reconnecting with true self

Gradually, the diary became aligned with the real me instead of the eating disorder, and authentic thoughts and feelings were regained.

Through sharing thoughts, that had previously been confined to my diary, with my therapist, I received guidance in recognizing and separating the eating disorder thoughts from my own true thoughts, and began using the diary increasingly as a tool to help connect more with true self.

For instance, the eating disorder would catapult a slight criticism or negative observation that was not meant in a personal way, into a catastrophe of WWIII magnitude. Thoughts would scream “you are useless!”

(Today, when feeling criticized or things are not going as planned, rather than default to an eating disorder thought and behavior, I write in my diary about how I feel – and why, why, why – releasing the pressure of the moment, until the thoughts slow down and I can see the situation rationally, and more clearly.)

Did others feel the same as me?

The ingrained self-abuse gradually declined as my body progressively, over the next 19 years, developed healthy thought and behavioral patterns.

Upon re-entering life’s mainstream, I wondered if others had found the diary helpful.

I found scant reference in the literature on the effect of diary writing in eating disorders, and even less about its role in disconnecting and reconnecting the body with self. This revelation, together with that of realizing the diary had at times aligned with my illness instead of me, led to the writing of The Diary Healer.

Facing a harsh reality

If queried, during my illness, I would have strenuously denied my diary was harboring secrets, especially from me. It was my friend and confidante, after all. But the harsh truth was the illness that invaded my mind also invaded my diary, causing a magnet-like focus on food as a tool for getting through each day.

Secrets and lies feed guilt and shame

The illness weakened authentic self by creating secrets within secrets. Rational thought all but disappeared. My diary records the transformation from an honest, eager-to-please little girl to a shell of myself telling lies, not only to my mother (“Yes, I ate the sandwiches you packed for my lunch”), but also to myself. In fleeting moments of clarity, I would feel overcome with guilt and shame. The eating disorder fed on this, too, causing more isolation, more dependence, on the diary.

With the diary as keeper of eating disorder plans and schemes, lies to family, friends and self, became increasingly conniving and subversive.

As years passed, the diary charted the secret toll of trying to function outwardly, while inwardly a slave to the eating disorder.

Embracing the truth

Recovery could occur only when each secret was painstakingly located and revealed, for an authentic life requires embracing the truth.

Diaries of others revealed experiences of the same inner hell, with their diary, like mine, a survival tool but also a collaborator in maintaining the illness.

As an inpatient, Renee had one diary for group sessions, and another for personal use. Her group diary assured staff she was “on track;” her personal diary was where she recorded the revulsion of seeing her weight rise.

Renee writes:

“This secret diary allowed the tears to burst open for they too were in secret.”

Externally, Renee’s group diary gave the impression to the outside world that she was “getting well,” “recovering” like she should. But internally, as reflected in her private diary, the eating disorder continued to dominate her mind, demanding secrecy.

A place to release thoughts without being judged

Especially when having attempted, as a child, to share worrisome thoughts and feelings with adult caregivers, and being dismissed, gaining confidence to share with others in adulthood, can be a challenge. The diary can assist in taking this courageous step.

Importantly, even before you can trust your own identification and expression of thoughts and emotions to others, you may begin to foster trust through a diary dialogue. The first step is to learn the diary can provide freedom for self-expression without judgment or criticism from external sources.

Gradually, diary entries reflect reintegration with true self. Rules aligned with the eating disorder disappear and feelings are acknowledged, explored and recorded. Here I write,

The process of writing about innermost experiences allows for this release of emotion. Rules continue to be made and broken, but the frequency declines as true thoughts are released into the diary.

Furthermore, the rereading or retelling of these experiences enables healthy components of self to be identified, emotionally processed and strengthened.

Your diary becomes a teacher

This process of recording and reflection is important because when parts of childhood, adolescence and young adulthood slip by while entrapped in a mental illness or debilitated by trauma, there is much life learning and experience to catch up on. My diaries became teachers, helping to let go of rules and discover and experience life as “me.”

Re-awakening of self is a tenuous process. Importantly, your diary can chronicle the gradual change from living by the Eating Disorder’s impossible rules, to locating, embracing, and learning to express and have faith in, thoughts and feelings that promote integration of your self and your body and, most importantly, are true to You.

To be continued next week.

Note

* Using Writing as a Therapy for Eating Disorders—The Diary Healer is the creative work in my PhD, which seeds discussion on how the diary can be integrated into treatment and recovery. For details, see https://lifestoriesdiary.com or go to http://acquire.cqu.edu.au:8080/vital/access/manager/Repository/cqu:13833