Mothers, daughters and eating disorders – stories to divide or conquer

Mothers, daughters and eating disorders – stories to divide or conquer

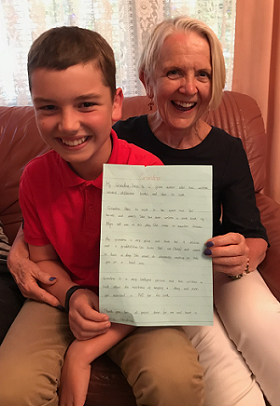

Mother and daughter, 2012. We arrived at a family function, not having discussed what we would be wearing. I feel this picture says a lot!

By June Alexander

Mothers, daughters, and eating disorders – the combination can be constructive or destructive. On Mother’s Day, 2019, I share thoughts on how facing an eating disorder together can be a beneficial release for both mother and daughter.

I developed Anorexia Nervosa (AN) in 1962 at age 11 and went on to develop chronic depression and anxiety as well. Nobody talked about my illness when I was young and I didn’t know I had an illness. I thought I was weak for not coping. My mother would say: “Why can’t you be like your friends?” At 28 I became suicidal, and fortunately my love for my four children under six, helped me to find the courage to tell a doctor for the first time about my inner feelings and battles. I feared the doctor would place me in an asylum and I would lose my children.

After five years of misdiagnosis, at age 33, I met a psychiatrist who understood my illness and me and became my rock during recovery. In a way that was only the start of my journey. I was on prescription drugs for the next 25 years as I went through the throes of reclaiming my shattered sense of self and identity. Often my career as a journalist was the only aspect of self that helped me feel at least a tiny bit sane.

I was 47 when my long time dietician, who spoke about feelings rather than food, suggested I work out which parts of myself belonged to me and which parts belonged to my illness. This was one of the most helpful suggestions in my long road of restoration. I took another eight years, becoming astute in self-awareness, and was 55 when I knew I had won my long battle to be me.

Relationships the greatest loss

Relationships were the greatest loss. My parents and sister did not understand my illness and my behaviour was embarrassing for them. I tried marriage three times. The first was lost to my illness, the second and third were disasters in that the men were attracted to the characteristics of my AN rather than “healthy me traits”. The result was constant chaos, which the eating disorder loved.

I think my parents thought me unreliable and irresponsible as they arranged to gift all of their large and valuable farming property to my sister and her eldest son and refused to give me any details. My parents’ deaths in 2009 and 2010 were a relief more than anything, because despite my efforts to encourage them, they had always refused to talk to me about the past. I needed to talk with them about the past, to allow healing to begin.

Two parts – the healthy me and the eating disorder

Reflecting, it is easy to see which parts of my life have been my illness and which parts have been healthy me. The two parts are very different! It has been a constant sadness for me that my parents and sister were unable to see this. However, on the bright side, it was their attitude that propelled me to devote the rest of my life to raising awareness of eating disorders so other families do not suffer the depth of loss and anguish as mine has done.

Regarding my children and their dad, George – they became my family and my life-savers. George re-partnered 35 years ago, but we remain as one as parents and share Christmas and our children and grandchildren’s birthdays and other family occasions together. We remain steadfast friends. In my low moments he remains a rock. George often said to me: stay away from your parents for they only bruise you (emotionally); your children are your family now. This became easier to accept as years passed – now my parents are dead and we are embracing the next generation, with grand children to love and enjoy. When my first grandchild was born 13 years ago, I feared I was not good enough to hold him, and feared my daughter would not allow me to take care of him. I wept the day she said: ‘Mum, you are Lachlan’s chief baby-sitter’.

It is no coincidence that since Lachlan’s birth, September 2006, I have ceased all prescription drugs for depression and anxiety.

My grandchildren love me unconditionally. They are an amazing tonic because they help me ‘be’ in the moment. They connect and give any eating disorder thoughts a big shove to the nether-sphere. ED does not stand a chance!

I have learnt to count my blessings and to focus on and cherish what I have; to think about what I have lost would be akin to inviting ED and death to my door.

The cost of shame and secrecy

For many years I did not want others to know about my illness. Mostly because I was highly ashamed of it. I was afraid I would lose my job if my employer found out I had a mental illness, and that colleagues and friends would think differently of me. I wanted to be ‘normal’ – I did not know then that such an attitude was enabling my ED to live on and continue its torment. For recovery, I know now that the eating disorder MUST be confronted and acknowledged.

(I cannot describe the enormous relief and comfort that evidence-based research has provided re revealing that AN is largely genetic). I could suddenly understand 40 years of my life.

Regarding my daughter, I worried about her when she was young – this was in the 1980s, before genetics were considered to have a role in eating disorders – and I knew her dad would provide the better environmental influence for her to grow to adulthood. So, she lived with him from the age of eight. Oh, the ache in my heart, where my daughter belonged. Such was the cost of my eating disorder.

Wanted: a mother without an eating disorder

Throughout her twenties, my daughter did not want to know about my illness – it had taken me away from her when she was a little girl and it took a long time for her to be able to understand why. All she wanted was “a mother”. A mother without an eating disorder. Initially she thought that if I spoke about eating disorders, even mentioned the name, I was asking for trouble (ED would come back bigger and more dangerous than before).

My books on eating disorders have been a big help in helping Amanda and other members of my family come to terms with and accept my illness and today my children accept and are supportive of my ED writing passion.

All they want is to see me, their mother, happy and they are happy, too. This is what they care about most and I am sure this is the same in most families. This is understandable and okay, but and there is a big BUT – eating disorders require constant vigilance; they MUST be acknowledged as the illness they are; every member of the family MUST be aware of symptoms and strategies. It is essential first-aid in achieving early recognition, intervention and diagnosis. Eating disorders thrive in darkness, silence and uneasiness. They thrive on dividing and conquering.

Sharing mother-daughter stories

Knowing when to share a story requires consideration of many factors. I think it is important to be upfront if a mother-daughter combination does go public together to share their stories as a way of raising awareness. It is important to acknowledge the possibility of relapse, putting it in same context as cancer remission and relapse.

To relapse is sad enough; to relapse in public is double sad and difficult (although the support can be greater, and you are showing that you are human – you are showing this can happen to anybody, no matter how vigilant you are – it is genetic, remember).

This is another angle to consider – do followers feel rejected and dejected when a shining star they have been following, suddenly fades and disappears from view?

I think the mother-daughter issue is worthy of more exploration. The mother is on a journey and so is the daughter. Both deserve support.

Sharing the healing journey brings many benefits

I have gone from being daughter, to mother and now to grandmother and I can see ‘it all so clearly now’! It is sad when the mother, as in my case, refuses for whatever reason to join the daughter on her healing journey. Unattended, the rift can grow and destroy relationships – causing alienation and estrangement that proceeds to the next generation. And then there are mothers who see the great need for collaborative healing not only in their daughter’s life but in that of countless others, and many lives suddenly have new meaning and mission.

Throughout my long journey I always felt that family support is crucial to recovery – I always felt I would have recovered much sooner if my family had been ‘travelling’ with me. Eventually, to regain me, I had to leave my parents and sister behind. This is why I am such a strong supporter of family-based treatment.

The family unit is the most precious social unit on our planet. Healthy and happy families lead to healthy and happy communities. With my own daughter, and my sons, I have always heeded the guidance of my psychiatrist – constantly telling them I love them, and cherishing every moment we have together – even when my illness was raging and I felt worthless. I eventually had to accept I had ‘lost’ my parents and sister, because they stayed in ‘the valley’ when I had to climb a mountain to survive, and having got to the top, my focus then had to be on building a life with my children and their children.

Personal growth for child and mother

An eating disorder can herald a period of unprecedented personal growth for the mother as well as the daughter. In fact, accepting this opportunity is often the challenge for the mother. The rewards, when the challenge is taken up, are great. The mother and daughter develop a bond of friendship and love that will last their life time and feed into and nurture the next generation. The alternative does not bear thinking about.

By spreading the message that mothers, more than anyone, are the biggest force in keeping an eating disorder at bay, we can help move mountains. Mothers need to know that they are not to blame, that there is support available to learn skills to cope with, confront and respond to not only their child’s illness, but also any of their own inhibitions and private sufferings. And daughters, as well as sons, depending on what age and stage they are at with their illness, need to know that on-going maintenance requires a team effort – if not with their mother, then their father, partner or children. Teamwork among families working with the treatment team is the best way to stamp this illness out. Recovery of self requires a village of care. I encourage you to join this village, this Mother’s Day.