Eating Disorders as Metaphors – it’s time for change

Eating Disorders as Metaphors – it’s time for change

It’s time to change our perspectives so we can think about eating disorders more clearly. That is, it’s time to move away from current interpretations of eating disorders that are largely contaminated with “metaphors”.

I am not referring to the therapeutic metaphors discussed in this article on The Diary Healer. Rather I refer to metaphors describing eating disorders such as a “vain girls’ illness”, a case of “extreme dieting off the rails”, evidence of “ethical failures”, and “a self-imposed disability that deserves neither care nor sympathy.”

Recently in a talk show the presenter, a popular Korean psychiatrist, suggested to a young K-pop girl group member that the girl’s serious bingeing habit seemed to be a kind of self-harm. The young guest burst into tears and I could appreciate the girl’s response immediately.

I was a young woman when, on October 18, 1997, an article titled Eating Disorders Go Global in The Los Angeles Times, stated: “Thirty miles south of the border with starving North Korea, young women in the South Korean capital are starving themselves, victims not of famine but of fashion.”[1]

I felt ashamed for being one of those girls

Such an observation may seem superficial and thoughtless today, but it was not considered so then. A newspaper cartoon described two girls from different parts of Korea, one from the north, terribly starved, and the other from the south, willingly avoiding eating with a huge scale beside her. The message inferred that girls in South Korea were ignorant and vain. Like, don’t they know how to think? Do they think, actually?

I felt ashamed for being one of those girls. I also felt ashamed when reading books, watching movies on television (TV), and hesitating without knowing what to do when Dad asked me to prepare drinks and snacks for him and his friend, already drunk. I faltered because, in contrast, at other times Dad treated me like his son and heir, better than his friends’ and relatives’ real sons who had little scholarly ambition, especially in the presence of others. So, who am I? Am I a first-born son substitute, a pseudo-boy, or just a girl, inferior and vain?

When the media ‘discovered’ eating disorders

Around the start of the new millennium, several investigative programs from major TV stations started to cover eating disorders as their subject. SBS’s “Unanswered Questions” advertised to recruit the informants. Like a possessed person, I wrote long pages of facts and references about eating disorders and emailed the document to the show’s scriptwriter. She answered promptly. She thanked me for the information and invited me to be interviewed, but I said, “No.” I didn’t want to be depicted in a possibly simplified, sensational narrative or to be identified.

So, the TV show was aired. It was the middle of summer in 2001[2]. I was an anguished college student and spent most of my time at the campus searching for the paper abstracts discussing eating disorders from PubMed, almost locking myself up in some computer rooms instead of attending classes. That eating disorders episode of the show was rather academic as it mentioned the “Russell’s sign” – instead of just calluses – and even presented the doorstopper of a textbook written by Garner & Garfinkel, certainly because I wrote about them in the document I had sent to the scriptwriter.

Young girls treated like they were in a freak show

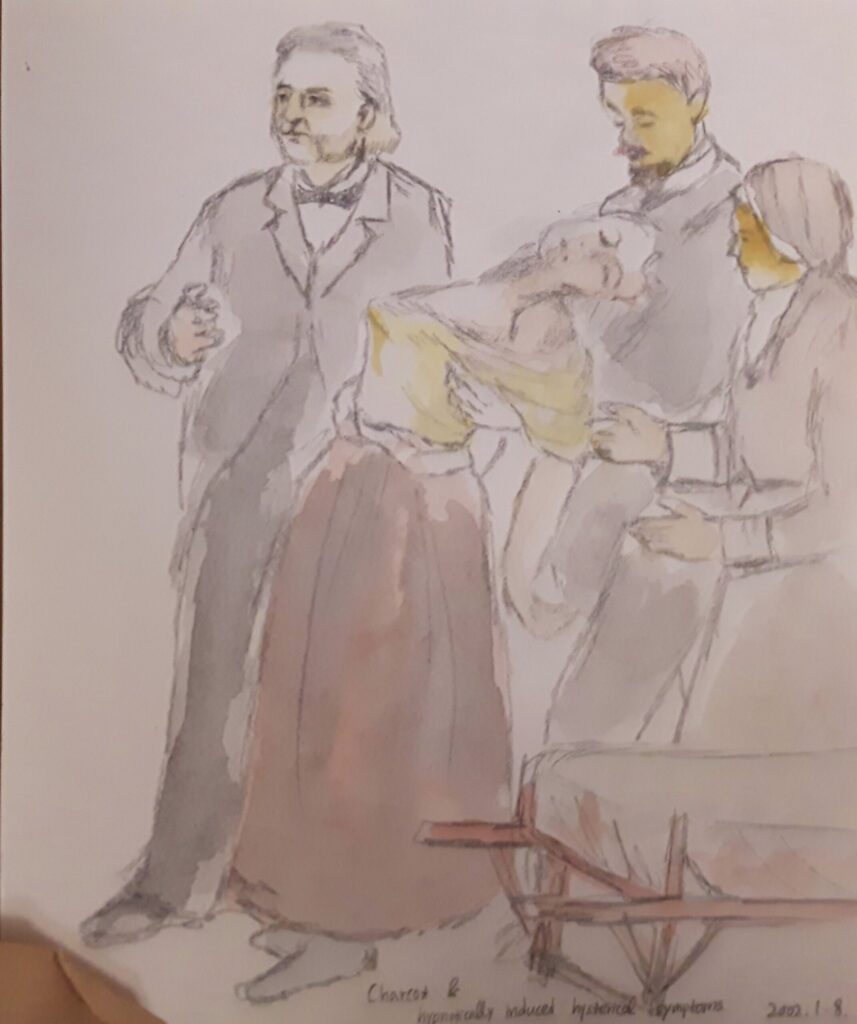

The show referred in its narrative to Korea’s three eating disorders clinics and their psychiatrists, the first generation of our country’s eating disorders experts. For that, I’m thankful to the production crews. The show covered Dr Kim Joon-ki’s summer camp outing with his day hospital patients and Baek Sang clinic’s Anti-Diet campaign. But that’s all. Several more documentaries and similar investigative programs followed, but that’s all. The struggling young girls were consumed by the media, like they were in a freak show. They were the 21st Century’s hysteria patients displayed for consumer-citizens like those women with symptoms demonstrated by Dr Charcot at the Salpêtrière.

Korea to have first national Eating Disorders Awareness Week in 2023

Twenty years passed and I, the young informant, was now in my 40s. I struggled at work because I hadn’t followed Dr Marsha Linehan’s advice not to disclose my stigmatised identity to potential employers before acceptance. I strived but failed for my expertise, gained by experience, to be acknowledged … failed, that is, until Prof. Kim Youl Ri suggested that I launch the first-in-nation Eating Disorders Awareness Week in early 2023. This project has been like a breath of fresh air for me. I drafted a short document first, under the title Seeing Eating Disorders in Systems:

Recently, The New York Times published an article titled Medical Care Alone Won’t Halt the Spread of Diabetes, Scientists Say[3], which sparked a lot of discussion. Although diabetes research and treatment technologies have advanced rapidly over the past 50 years, the prevalence of Type 2 diabetes among adults in the United States has increased from about one in 20 in the 1970s to about one in seven today. The article quotes Professor Schillinger of the UCSF School of Medicine as saying, “There is no device, no drug powerful enough to counter the effects of poverty, pollution, stress, a broken food system, cities that are hard to navigate on foot and inequitable access to health care, particularly in minority communities.”

“Our entire society is perfectly designed to create Type 2 diabetes,” Prof. Schillinger argues. “We have to disrupt that.”

So far, eating disorders in Korea have been considered as unusual neuroses of young women, insignificant diseases that are barely on the edge of social attention, vanity addictions that women obsessed with dieting can be easily given up if they “get their minds right”, or they exert proper “willpower”. Moreover, while “health” or “disease” remains regarded as a personal characteristic or a phenomenon that is nested within an individual, eating disorders are easy to be regarded as a kind of “ethical failure”. When the cause of a certain misfortune is attributed to the person, people tend to ignore their misfortune with the idea that they reap what they sow.

But what if, to get closer to the truth, we could take a systemic look at what has happened and what is happening now? Eating disorders have become prevalent in the past 20 years with surprising ripple effects, the age at which they are affected is much younger and the number of male patients has increased significantly. For what reason did this complex system of here-and-now become like a hotbed of eating disorders?

There is this neologism, ‘선망국(先亡國)’’, which means “a country already in ruins” and is rightly the cynical counterpart of ‘선진국(先進國)’, a developed country. As I recall, it was coined on Twitter like a meme years ago when people here in Korea witnessed almost the same political and societal failures as we had undergone already in other “developed” countries.

Illness struggle must not be allowed to become ‘normal’

It was this realisation that perhaps we had arrived in the dystopian future much earlier than others, that all our failures and disillusionment could become the normalcy for the wider world. Such a grim, surreal realisation can be personal, too. I graduated from university after almost six years with many interruptions of hiatus. Beyond that, I have persevered in my career of 17 years in a rather rugged way, with many short-term interruptions. Because of my illness struggle, I’ve been regarded as an undesirable, suspicious applicant at every job interview.

I notice that many of the younger generations seem to pursue a similar course, like mine. It’s alarming, even threatening, to see my experiences, having been considered as failure, to become closer to normalcy for them. So, I was kind of ‘선망인(先亡人)’, the person already in ruins, long before them who are following.

I find today’s situation threatening because I was a sick one, a patient, and moreover a difficult, chronic patient. But those young ones, who now share similar life experiences with me, are not. Why should it be that what happened to the underserved, neglected one now becomes the future for everyone? Why do I have to see more and more people suffering from eating disorders without any improved access to proper treatment?

I read this quote from C. G. Jung recently on the web:

Suffering tends to isolate you. However, understanding of it may lift you up somewhat. In the case of psychological suffering, which always isolates the individual from the herd of so-called normal people, it is of the greatest importance to understand that the conflict is not a personal failure only, but at the same time a suffering common to all and a problem with which the whole epoch is burdened. This general point of view lifts the individual out of himself and connects him with humanity[4].

Analytical Psychology: Its Theory and Practice: The Tavistock Lectures. (1935). In CW 18 (retitled) “The Tavistock Lectures” P. 116

Look at them and look at me

Look at them and look at me. Pay attention to what people with eating disorders are really going through and what is really happening. All without the images and fixed ideas regarding the lexicon that is eating disorders.

I’m thinking about what we can do if we start from zero, like an inquisitive, clear-eyed novice, rather than from an individualistic diagnosis. We can deviate from the illness as metaphor. The one thing I’ve learned from my difficult years struggling with an eating disorder is this: Never let the conclusions (of others) stop your own questioning.

[1] https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1997-oct-18-mn-44049-story.html

Retrieved from https://www.healthyplace.com/eating-disorders/articles/eating-disorders-on-rise-in-asia

[2] https://www.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2001/07/06/2001070670213.html

[3] https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/05/health/diabetes-prevention-diet.html

[4] https://carljungdepthpsychologysite.blog/2022/08/19/if-a-man-is-lost-in-the-desert-or-quite-alone-on-a-glacier/